08Jun

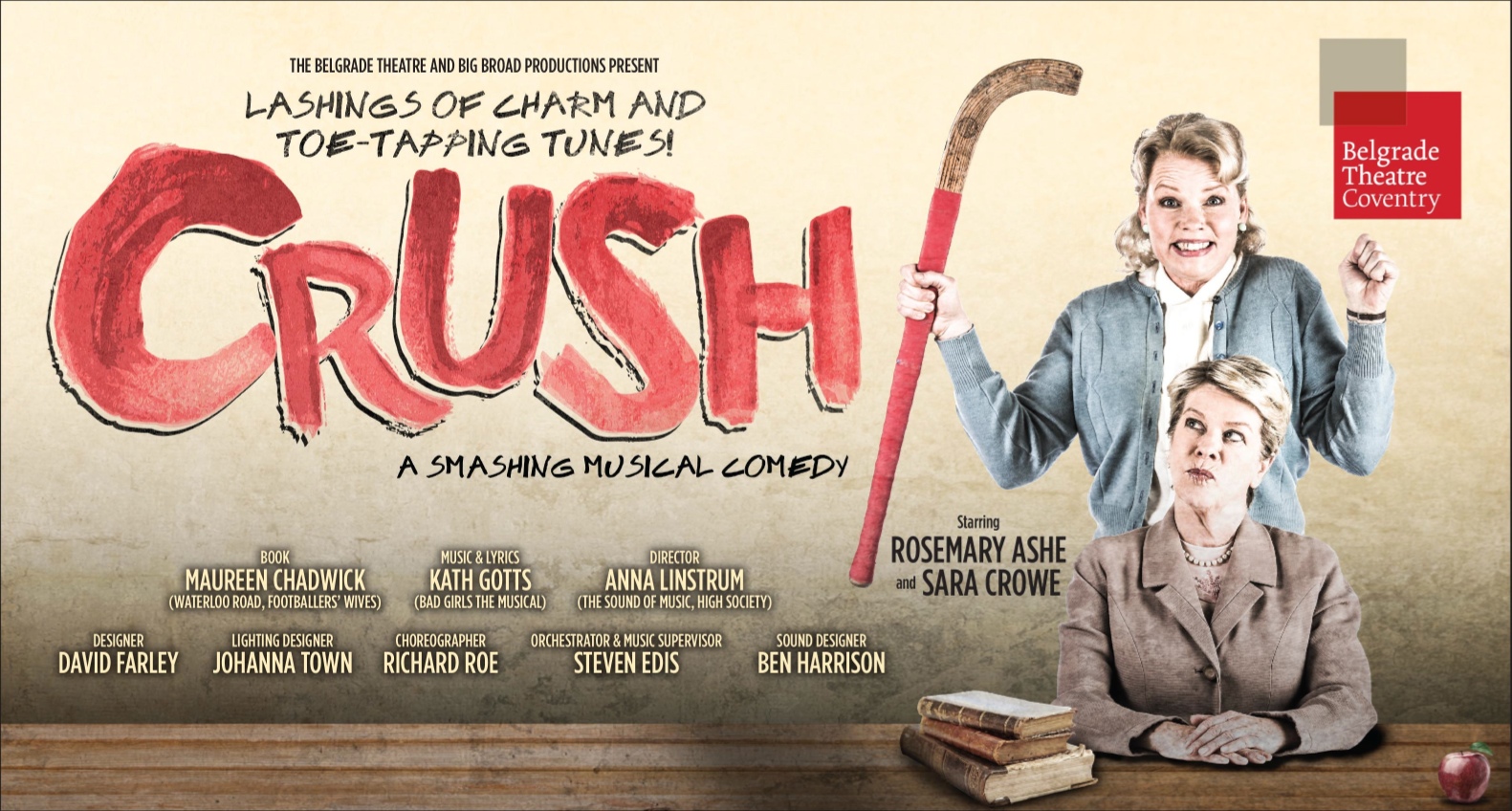

Crush and the Girls' School Story

CRUSH AND THE GIRLS’ SCHOOL STORY

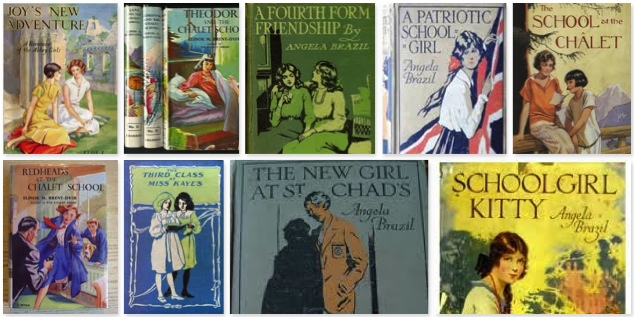

The popularity of girls’ school stories has always been an embarrassing enigma to mainstream critics. It is often claimed that Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days (1857) was the first British school story, with girls’ school stories following only after educational opportunities were extended to girls in the later nineteenth century. In fact, Sarah Fielding’s The Governess or The Little Female Academy (1749) preceded Tom Brown by more than a century, and girls’ school stories have always been more significant than boys’ in terms of number of titles, popularity and sales.

There is a good reason for this. Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, middle-class girls were denied an academic education and were trained instead in the feminine virtues to be helpmates of men. The girls’ school story as we know and love it was a product of the early feminist movement to create educational opportunities for women in schools and universities and to fit them for paid employment and independent lives. Far from being the embodiment of respectability, restrictiveness and outmoded values that they later came to represent, the schools – the Girls’ High Schools and the public schools like Cheltenham Ladies’ College, Wycombe Abbey and Roedean – were radical and feminist in their recognition that knowledge is power and their insistence that girls be educated beyond married dependence. The books captured this spirit and so does Crush, where the founder’s suffragette vision is contrasted to the interloper headmistress’s invocation of regressive ‘Victorian values’.

The authors of girls’ school stories were themselves beneficiaries of this emancipation through education: jobbing writers in the main, they supplied an eager, growing market of school and working girls with a product at first viewed as harmless, if not morally sound and character-building. Their readers were generally girls who did not (and would not have been able to) attend the deliciously attractive boarding schools depicted, who received the books as school or Sunday school prizes and later, drawn into the fantasy world, saved their pocket money to buy additions to their favourite series or requested them as birthday or Christmas presents. No one took much notice of their innocent pleasure until the subversive power of girls’ school stories began to be recognised just before the Second World War and the backlash began. Within a decade the genre had been practically wiped off the publishers’ lists and those girls who had loved the books, and the women who went on loving them, had to fall back on nostalgia and the second-hand market.

Why have so many girls and women (and some men) loved the books, even up to the present day? And why did the books have to be denigrated and forcibly suppressed? The answer to both questions is the same. We loved them, and they had to go, because they depicted all-women worlds in which men were not the centre of women’s existence – were, indeed, largely decorative or superfluous – and where women could occupy any and every role requiring skill, courage and leadership. Naturally, in a patriarchy, this is quite wrong; women should be followers, not leaders; women should be dependent and in need of protection, not independent and brave; women should devote themselves to men, not to self-development or – God forbid – to other girls or women.

The destruction of girls’ school stories took many forms. One was the reinterpretation of the ‘crush’, the focus of this musical. In early school stories, such as those by Angela Brazil, girls’ hero-worship of other girls or mistresses is treated simply as a plot device typical of girls’ schools, quite neutrally, but in the 1920s, under the influence of the new ‘science’ of sexology, it came to be decried as immature and, later, unhealthy. It took the sophisticated parodies of male satirists like Lord Berners (The Girls of Radcliff Hall, 1936), Philip Larkin and Arthur Marshall to make an overt link with sexual deviance, but the critics quickly took this up, and by the 1970s everyone was sniggering at the ‘lesbian’ content of so many of these books. ‘One must assume that these authors … had not the faintest idea in this instance what they were writing about,’ observed Gillian Avery in Childhood’s Pattern (1975). In fact, I suggest, these authors knew very well that they were writing about love between women, but did not see it as pathological.

Many school story enthusiasts have mixed feelings about the masculine camping-up of school life in Arthur Marshall and Co.’s work, which often seems to mock rather than celebrate women and their all-female world. When women write such parodies, however, the tone is more sympathetic: Nancy Spain’s Poison for Teacher (1949) (also set in ‘Radcliff Hall’, in this case based on her own school, Roedean) casts a critical but indulgent eye on both the institution and the genre; she was certainly writing consciously as an insider and a lesbian. Different again, because possible now, is the approach in Crush, where the lesbian content is neither satirised nor parodied: rather, it is central to the narrative and resolution of the school’s fight to defend its progressive values.

Fans of girls’ school stories will recognise many of the motifs in this show: the tyrannical replacement headmistress, the benefactors in disguise, the girls who run away and the school sneak who redeems herself. But the humour is also characteristic of the later school stories. As Sue Sims has noted in The Encyclopaedia of Girls’ School Stories (2000), it is a mark of maturity when authors feel free to mock established institutions that matter to them. Sims locates the shift in treatment in the later interwar and post-war period, which many consider to be their golden age, when girls’ school stories become ‘deliberately funny; the idealism and seriousness of many of the 1920s books are gently held up to ridicule’. At the same time, the ironic tone masks the original steely message: that education matters, that girls matter, that women matter, for themselves and not simply in relation to men. The books kept their popularity through the second half of the twentieth century because this message became ever more important, and it is a message that still resonates forcefully today.

Professor Rosemary Auchmuty FRSA, Author of 'A World of Girls: the Appeal of the Girls' School Story' (London: The Women's Press, 1992, 2nd ed.2004) and 'A World of Women: growing up in the girls' school story' (London: The Women's Press, 1999, 2nd ed.2008).